Recently, Norwegian TV2 published an article on Temu, raising serious concerns about the company’s links to forced labor. The report has sparked public debate about how Norwegian consumers and lawmakers should respond.

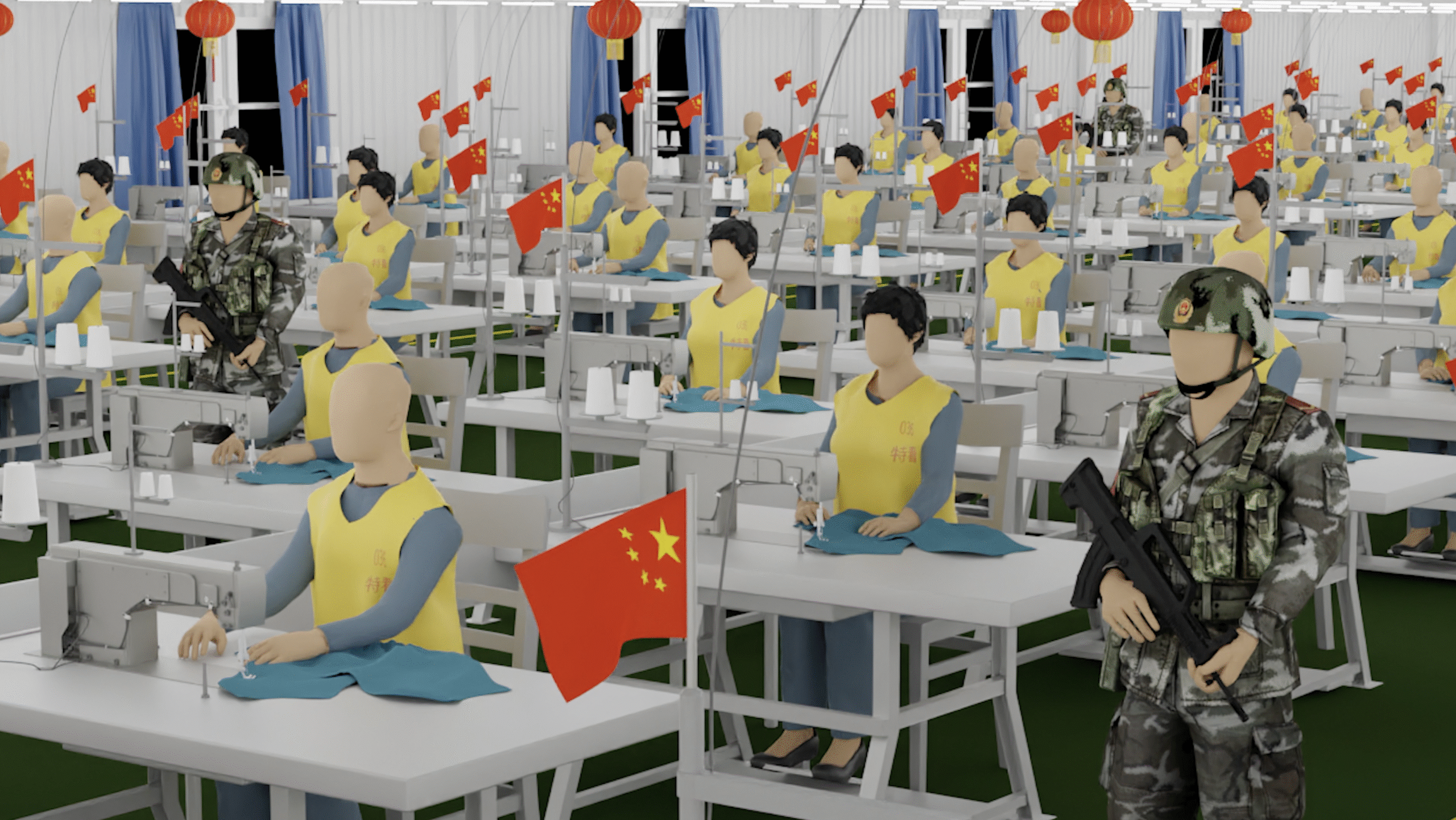

In response, Adiljan Abdurihim, coordinator of the Uyghur Transitional Justice Database (UTJD), highlighted that this issue is not isolated to a single company or sector. “Forced labor is not just a problem in one area like retail,” he explains. “It reflects a much larger pattern across global supply chains — especially those tied to East Turkistan. Many industries, from textiles to solar energy and electronics, rely on materials and products originating from places where Uyghurs and other minorities are forced to work under coercive conditions.”

Abdurihim points out that Norway’s Transparency Act, which was used by UTJD to scrutinize solar companies, is a step in the right direction but far from enough. “More rigorous laws and enforcement are needed,” he says. “Companies must be held accountable for what happens at every stage of their supply chains — because this is about basic human dignity and rights.”

He also reminds consumers that the power to drive change doesn’t only lie with lawmakers or companies. “When people become more aware of the true cost of these products,” Abdurihim adds, “they can choose to support businesses that take ethics seriously. That’s how we begin to tackle forced labor on a larger scale.”

The Uyghur Transitional Justice Database (UTJD) published a report in 2024 examining the links between Uyghur forced labor and the Norwegian solar panel industry. The investigation was made possible by Norway’s Transparency Act, a legal framework that allows civil society and the public to scrutinize the ethical background of companies’ supply chains. This law provided UTJD with the legal grounds and practical space to reach out to 20 solar companies and inquire whether they could ensure their supply chains were free from forced labor or from raw materials, such as metallurgical-grade polysilicon, nearly 24% of which is sourced from East Turkistan as of 2023, where such abuses are prevalent. The findings revealed a troubling lack of transparency: only five companies responded, and even those responses lacked sufficient clarity, while 15 remained silent. This outcome highlights both the significance of the law and its current limitations in promoting meaningful corporate accountability.

Although UTJD has made its focus on the solar panel market, other industries in the Norwegian market are still open to investigation, as China dominates key global industries with heavy sourcing from East Turkistan, raising forced labor concerns. Over 80% of China’s cotton, which is 20% of the global supply, comes from East Turkistan (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-56535822). In solar, 35% of China’s polysilicon (75% of global output) is sourced there (https://www.shu.ac.uk/helena-kennedy-centre-international-justice/research-and-projects/all-projects/over-exposed). Not only garments and clean energy but also food products are complicit, where up to 17 UK and German retail products, including tomatoes, were investigated and proven to be made with Uyghur forced labor (https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/crezlw4y152o). Another investigation found that 76 pharmaceuticals exported from China are solely made in East Turkistan(https://c4ads.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/SideEffects-C4ADS.pdf). Aftenposten reported that Oslo’s Ruter acquired 22 electric buses from BYD, a Chinese company tied to forced labor as well (https://www.aftenposten.no/oslo/i/P4M9Ke/elbusser-i-oslo-kobles-til-tvangsarbeid-i-kina).

With this scale of a heavy presence in the western and EU countries of Uyghur forced labor-made products, a company like Temu is not immune to such exploitative practices. Temu is an online retail platform owned by PDD Holdings, which also operates the Chinese e-commerce site Pinduoduo. The company’s supply network includes over 80,000 suppliers, facilitating millions of small package shipments to U.S. consumers annually. The platform is valued at an estimated $100 billion. (https://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/fast-fashion-and-the-uyghur-genocide-interim-findings.pdf)

Although it is not confirmed whether the company is benefiting from Uyghur slave labor or not, there are concerns about the company’s ethical background. a Tel Aviv-based firm, Ultra Information Solutions, identified at least 10 products on Temu that were made or sold by businesses located in East Turkistan, with obscured supply chain origins.(https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-06-13/temu-sells-products-in-us-linked-to-forced-labor-in-china-s-uyghur-region)

According to the Selected Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, Temu does not conduct audits or operate a compliance system to ensure adherence to the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA). The only stated precaution is that sellers agree to boilerplate website terms that prohibit forced labor, without any explicit reference to UFLPA, “Xinjiang”, or related legal standards. Temu admits it does not prohibit sellers from offering products sourced from E.T. The committee’s findings also show that Temu has no independent system to verify whether its suppliers are compliant with UFLPA or other labor laws. The platform’s current “compliance” mechanism relies entirely on suppliers self-certifying through its Third-Party Code of Conduct, which is vague and non-binding. In short, there is no monitoring, auditing, or enforcement mechanism in place to vet suppliers or prevent abuse. And an interesting finding that proves the company’s serious lack of transparency is that Temu touts a public reporting system where consumers or regulators can file complaints about violations. However, the company reported no complaints related to forced labor.

UTJD was able to take a few steps towards addressing the Uyghur forced labor concern with helpful tools such as the Transparency Act, yet, there should be more efforts taken, not only in the Norwegian solar market but across all industries in Norway. Without robust legal measures, comparable to the United States’ Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), Norway risks becoming a dumping ground for products rejected by countries with stronger human rights standards. Prioritizing stronger regulations is not only a moral imperative but essential to aligning with international norms on ethical sourcing and corporate responsibility. Therefore, Temu should be further investigated, and Norway should take the needed measures to do its part in ensuring it does not consume forced labor-made products.

We encourage Norwegian consumers to think critically about whether ethical working conditions have been maintained in the production process of goods from China. We believe that the Norwegian state must impose stricter requirements on Temu and other goods manufacturers in China: They must themselves prove that their goods are not produced using forced labor or under working conditions where those working on the assembly line are grossly underpaid. The Norwegian state must ensure that Norwegian consumers can buy Chinese goods without a guilty conscience.