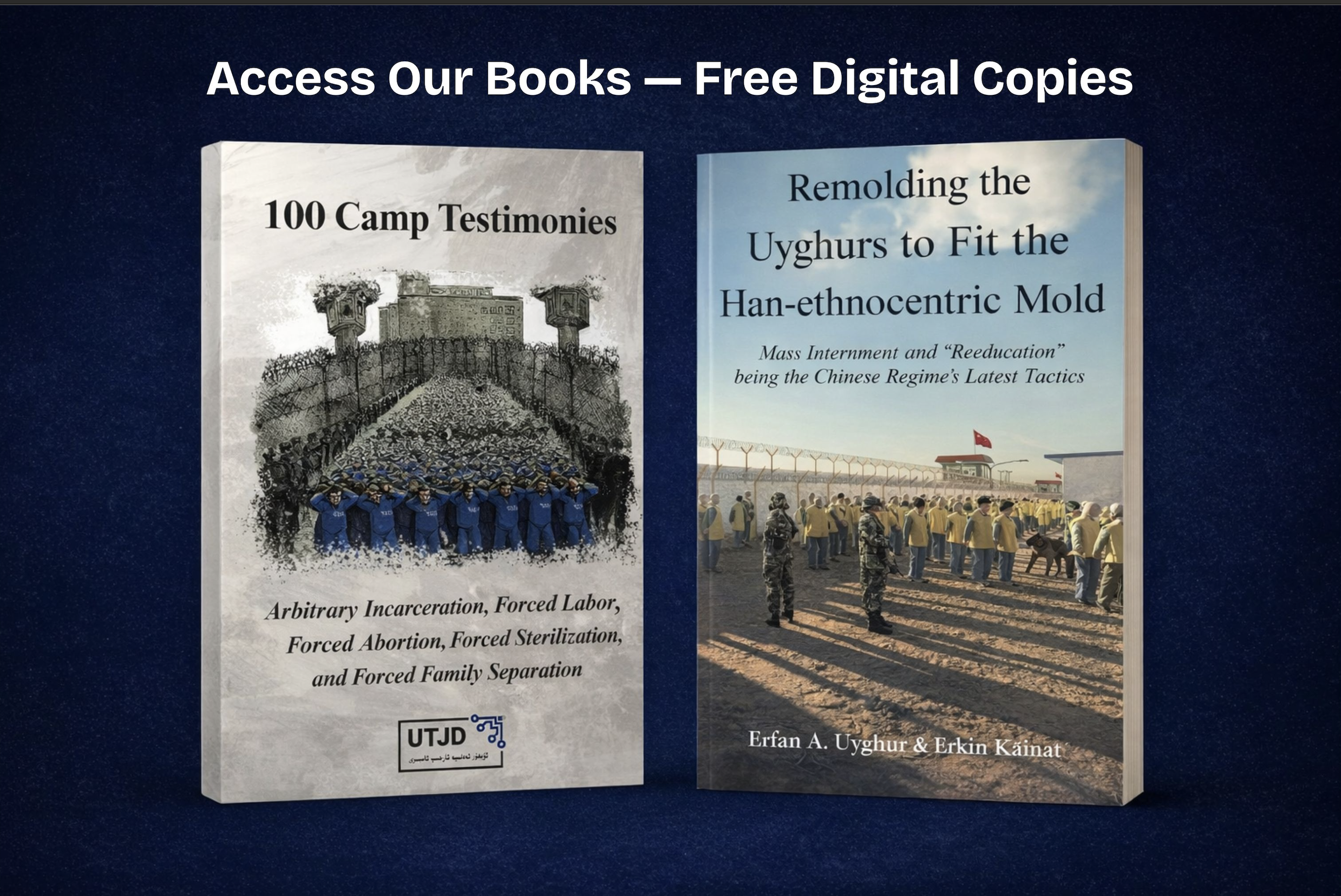

A testimony from our “100 Camp Testimonies” Book

I was born in 1997 in Khotan, East Turkistan. I came to Turkey with my sister in April 2016. My sister and I attracted unwanted attention of some Han Chinese officials in Khotan, who visited our house two or three times a week and flirted with us. Some would just break into our house at nights without knocking or asking for permission. They, with shameless audacity, even asked my father to provide one of us to them. They did not have the intention of marrying us, but only wanted to satisfy their animalistic desires. My father could not stand them, so he took us out one night without telling anyone, and sent us to Turkey. As of 2021, my sister and I are studying at a university in Istanbul.

I would like to give testimony about what I had witnessed and experienced in Khotan, East Turkistan, and testify for my family and relatives.

As far as I know, the Chinese regime’s internment campaign started in late 2014, during which time Uyghurs in Khotan were taken to Zhejiang prison, Qaraqash prison, or detention center (close to Khotan Finance Bureau 和田市财政局), and were held for two or three months in the name of “reeducation.” A portion of the Uyghur population in our community was subjected to forced labor, including both young adults and elderly men. The men who were too old to work were taken to the village office and forced to endure the sun’s rays all day long during the hottest time of summer, and my grandfather was also among them.

Those who were subjected to internment and forced labor were innocent people, and they never committed any crime. The local authority forced the men who were not taken to do some silly tasks, e.g., moving a small pile of sand five meters using only hands, without a spade or shovel. In Fall 2014, I also went with my father once to help him do the silly task, and there were about 200 to 300 farmers there. It was forbidden to pray by yourself or in groups, and it was forbidden for four or more people to assemble. We were under constant police surveillance.

In early 2015, Ghulam Ali Imamniyaz (born circa 1989), my uncle (my father’s younger brother), was taken to an internment camp. It was supposed to be a two-month-long reeducation, but according to my uncle, they were not taught anything while being held there; the internees were not even properly fed. On top of that, we were asked to pay for the internment expenses. We were allowed to meet my uncle at 1 p.m. every Sunday, and the camp officials would ask us to bring food to my uncle. The Chinese regime interned our loved ones and we had to pay for the unjust incarceration. My uncle was released in early May 2015.

After midnight at around 1 a.m. (May 24, 2014), the police banged our door shouting, “Open up!” After my father, Tursunbaqi Imamniyaz, opened the door, the police said, “Put on your clothes and we will take you to the village office.” Soldiers entered first into our house, followed by the police, who were then followed by the village officials, and in total they were 20 to 30 people. The soldiers climbed over the walls and broke into our neighbors’ houses, and dragged our neighbors out of their houses and beat them in their front yards. At least one man from each family was taken that night, and in some families the number was around four or five.

The next day, we went to look for our father but could not find him. He simply disappeared. When we asked the village officials, they told us that they did not know where my father was taken to. For the following 16 days we tried to find our father, and after bribing some officials, we were informed that our father was taken to Qaraqash County prison. Eventually, we got our father out of that prison after giving more bribes.

My father told us what had happened after he was forcibly taken away from our home. When he was taken to the village office, they put a black hood over his head, and packed the big military style transport vehicle with all newly detained Uyghurs including my father, while kicking and shouting at them. Along with other detainees, my father was taken to a detention center, where he was held for eight days. They put 30 to 40 people in a tiny cell that was meant to hold six detainees, and it was so crowded in there that even standing upright became a challenge. The detainees were subjected to all sorts of abuses, both psychological and physical abuses as well as deprivation of food. My father could hear women scream, and he told us that his friend’s father was electrocuted to death in front of him.

After being held for eight days, the detention center reached maximum capacity as more and more Uyghurs were being detained and sent there. The authority started sending the detainees to the neighboring counties and cities. My father and a few more people from our village were sent to Qaraqash County prison. They were forced to sit still with lowered heads, i.e., raising their heads or talking to one another was forbidden. After being held for 16 days or so in total, my father was released. However, he was detained again and taken to an internment camp in Lasköy town (拉斯奎镇) of Khotan, where he was held for two months. The internees were not taught anything; rather, they were subjected to constant psychological abuse, e.g. the camp guards would say to them, “You all deserve death.” They also threatened my father by saying to him that they would detain his daughters (i.e., me and my sister) and torture them there.

After my father was released, my elderly aunt was detained. She was released after three days as she was in poor health. They tried to intern my father again, but before that happened, he went to the northern part of Khotan to avoid internment. He returned home around November 2014, during which time the Chinese authorities nullified all ID cards, so we had to apply for new ones. We went to our local authority in Qaraqash for our new ID cards, but when we entered the police station, the police shouted at my mother, “Don’t you know what kind of place this is? How dare you wear a headscarf!” They pulled her hair and beat her in front of us.

In mid-November 2015, we were summoned to the village office, where we met some officials who were from the “special work group.” They collected our blood and DNA samples, and when I asked the purpose behind this collection of biodata, they said that in doing so they could find us wherever we went, also in the event of solving crimes.

From early 2016 the random night raids and unsolicited visits became even more frequent. Armed soldiers would enter our house and carry out their search, followed by the police who would check again, i.e., they checked every nook and cranny of our house to see if there was any hidden space left unchecked. Sometimes they even carried out some digging. When they could not find anything suspicious, they would leave. We got so scared that we started going to bed with our clothes on. Whenever they came, my younger siblings always tried to hide themselves as the police always beat children and scared them with their weapons. The police started to notice us girls, especially me as I was the elder one, i.e., we got a lot of unwanted attention. The Han Chinese police often threatened my father by saying that they would do this and do that to us, i.e., his daughters.

In March 2016, my father and my uncle were taken to the village office and tortured there, i.e., getting beaten repeatedly with an iron bar on their backs. The reason for this retaliatory action was that my father refused to provide his daughters to the police to satisfy their sexual desire. After my father came back, he immediately bought us plane tickets to Ürümchi, where we stayed for nine days. On April 8, 2016 my sister and I arrived in Turkey. My father was supposed to bring my mother and my other three younger siblings afterwards, but my three siblings were not issued ID cards as they were born illegal according to the Chinese regime’s birth control policies, i.e., my parents have three more children than the officially approved/allowed number of children, which was two.[1] Although my parents had paid hefty fines for having three more officially unpermitted children, my three siblings were not issued national ID cards. Since they did not have ID cards, my parents could not get them passports. My father told us that they would join us in Turkey after they got the passports, which never happened. On January 4, 2017, my mother called my aunt in Turkey, telling her that, “We cannot contact each other anymore.” We have not been able to contact my family ever since.

In August 2017, we bumped into our neighbor’s daughter in Istanbul, who told us that our father was sentenced to nine years in prison. A cousin (female) of us was also sentenced to nine years in prison. Our mother was taken to an internment camp, while my three younger siblings disappeared. Our other (female) cousins, who were under 18 years of age, were also taken to internment camps.

After my father sent us to Turkey in 2016, my family was under tighter police surveillance. The local authority confiscated our family’s properties because my father had sent us abroad. In July 2017, when my grandfather went to the local police office to do an errand, he was subjected to severe abuse. He suffered so much that he died the day after. As our family was blacklisted by the authority and labeled as a “criminal family,” people in our community were not allowed to attend my grandfather’s funeral.

We lived together sharing the same yard with our grandparents and the families of my father’s siblings, and we were 33 people. I learned that only one of my uncles, his wife and my grandmother were left alone, while the rest of our big family were either imprisoned or taken to internment camps. The children were taken to a state-run orphanage, or orphanages. I later recognized one of my little cousins after seeing the photos of a state-run orphanage on the internet.

Already in 2013 and 2014, Khotan was under heavy police surveillance. For example, our family house is close to the highway in Aqtash area (阿克塔什) of Lasköy town, and military vehicles and black police jeeps were stationed 24/7 on that highway, acting as a checkpoint. Sometimes when we came across them, they would harass us with derogatory words or behavior, with their weapons pointing at us. We were so frightened that we stopped going out. Our father also did not allow us to go outside due to the constant harassment of the police.

In addition to the black jeeps, the police would also use motorbikes to patrol the narrow streets or alleyways. In late 2015, two policemen on motorbikes chased me into one of the narrow alleyways, and caught me at a place full of people fortunately, and got my phone number. On many occasions the policemen sexually harassed Uyghur girls in the narrow alleyways. In the summer of 2013, when I was having a snack on the side of a road, I saw policemen grab a girl from the street and put her in their black jeep while she was screaming the whole time.

At that time, policing in the Khotan city was different from that in the countryside. In the city, people could go about their daily businesses. Since 2012, women’s black dresses, star and crescent clothing, wearing a headscarf that was tied under the chin were forbidden. Women in black clothes were not allowed to take public transport, and they would be detained on the streets, or their long dresses would be cut short. Headscarves were not allowed in schools or language training centers. The police in the city looked a bit normal, while the ones in the countryside were very different.

Starting from 2014, every official in a village was given an order from the higher-ups to send Uyghurs to the detention centers or internment camps, and they had to meet numerical quotas. For instance, the first wave of detainment came to those who had previously disputed the police or party officials before 2010. They were blacklisted in the system, and not allowed to travel outside of the city. Instead, they needed a green card issued by the authority to travel outside of the city. Since they were blacklisted, they were not issued a green card at all.

For those who were not blacklisted and wanted a green card, they needed to collect official stamps from 10 or more different authorities. The Uyghur village officials who had detainment quotas to came to our house to ask for “help.” They detained one person from each Uyghur family to meet their numerical quotas.

In the countryside, the practice of using Uyghur forced labor was quite rampant. Those who were not interned were likely to be subjected to forced labor, including women.

If one Uyghur individual wanted to get something done at the village office, they would not be allowed access to the building unless they pay 50 or 100 RMB (roughly US$7.9–US$15.8) to a Han Chinese police; moreover, offering them alcohol and tobacco almost became a must-do requirement. If such unwritten requirements were not met, the person in question would be sent to an internment camp or other places, or beaten by the police on the spot.

In the countryside, the police would often beat Uyghur kids or hit them with their cars. I did not see any police run over a kid, but I heard such stories from our neighboring village. The way people were treated in the city was totally different from that in the countryside, i.e., people in the city could lead a little bit of a normal life, but people in the countryside did not have a normal life at all. This difference has persisted til today (2021), so I heard. Our family legally ran a small trade business, and we were forced to provide food and groceries for our village officials, regardless of our financial situation. At some point, the local authority wanted to build large-scale greenhouses in our village. As a result, our house was demolished, and our land was confiscated. With the money that we got compensated for we could not even afford to buy back a third of what we lost. I do not know where my family address is now, or where they are staying at.

As far back as I can remember, all Uyghur women in our village were subjected to forced pregnancy tests, which used to be carried out every three months, but now every month. If an Uyghur woman who already had two children did not show up for the test, the whole family would be punished. The Uyghur men would be incarcerated, while the Uyghur women would be used as forced labor.

I was arrested for the very first time when I was eight years old, then again when I was 11, and again when I was 14, the reason for which was that I learned how to read Koran and studied Islam. At that time, there was one supervisor who monitored 10 Uyghur families, and one such person informed on me. One day while I was playing in the front yard, a policeman banged our iron gate. I was only eight years old at the time and he scared me a lot. He asked me to open the gate, but my parents locked the gate from the outside when they left the house. He then climbed over the wall and handcuffed me while pressing me to the ground. I did not know what was going on. I was taken to the Lasköy police station, where they forced me to kneel on the hard concrete for several hours. Due to the beating and kneeling, I had suffered skin issues at that time, and I still have some scars on my skin sustained from that abuse.

My uncle came to the police station asking for me, and he was severely beaten while I was watching. They only stopped beating him when he lost his consciousness. The policemen seemed to be happy after beating my uncle, saying that how satisfying it was.

When I was 11 years old, I was detained again for reading Koran. The police made me sit in a hard chair for 25 hours, without giving me any food or water.

When I was 14, my cousin was pregnant with her third child, which was not allowed by the Chinese authority. If they found out about it, my cousin would be subjected to forced abortion, regardless of gestational age. Because of that fear, I went to the routine pregnancy check instead of her. My cousin used to cover her face, so I covered my face as well. The police shouted at me, “You are a terrorist, and you have the rottenest ideology among these people around here.” They verbally abused me and I was held for two days at Lasköy police station. My father rescued me after paying some money to some official.

One summer when we paid my aunt (my mother’s sister) a visit, the police brought the dead body of a girl to our neighbor, i.e., the daughter of my aunt’s neighbor. When the police were moving the body from the trunk, her hand was briefly exposed. I saw a bloody red hand without fingernails, which could indicate a sign of torture during detention. Her parents fainted when they saw their daughter’s cold dead body. She was only 16 years old at the time, while I was 13. According to my aunt, a few days before the tragedy, the girl tried to go through a checkpoint to another village, and a few policemen sexually harassed her. She got angry, and was drawn into a quarrel verbally. In the end, she returned home without going through the checkpoint. Three days later, the police went to her house at night and detained her. She was raped and severely tortured, with bite marks all over her body. After her burial, the police had kept guard over her grave for a month. Normally, in our tradition we would bury a dead body in a dry place, but the police deliberately buried her in a wet place next to a stream. They were afraid that someone would take a photo for evidence.

Below is a list of my relatives who are either in prison or in internment camps:

Tursunbaqi Imamniyaz, my father, was born on April 15, 1972, who was detained in April 2017 and later sentenced to nine years in prison; he is probably held in a prison in Korla. He was first arrested in the evening of May 24, 2014 and sent to a detention center in Khotan city, and 10 days after his detention he was sent to Qaraqash prison, where he was held for about a month. We bribed various officials in Khotan, and my father was released in late June 2014. He was rearrested in July 2014 and held in Lasköy prison for two months. He was released in September 2014 due to his illness (developed ulcer in the intestines). He was also forced to go to the local authority (Dadui 大队) every morning at 6 a.m., and from 6 to 8 a.m. he was forced to stand outside in front of the Chinese flagpole and show his respect to the Chine regime. He and along with other Uyghurs were subjected to forced labor at the Dadui’s quarters, and were forced to stand in the sun during the unbearable heat of summer. This forced attendance at the local authority Dadui lasted two months.

Gholameli Imamniyaz, my uncle, was born in 1989, who was detained many times (nine times or so) between 2014 and 2017. Each time he was held in an internment camp for at least two months. The last time he was detained was back in 2017 (to meet the numerical quotas of our village officials), and he was sent to an internment camp.

Bunisa Imamniyaz, my aunt, was born in 1966, who was detained in 2017 and sent to an internment camp. Her husband Memetabdulla Abdurehim, born in 1965, was also interned around the same time. The reason for their internment was that their three children are in Turkey.

Eli Memetabdulla, my cousin (male), was born circa 1989, who was detained in 2017 and sent to an internment camp because he has some family members living in Turkey. He was later sentenced to seven years in prison.

Aygül Memetabdulla, my cousin (female), was born circa 1990, who was detained in 2017 for having traveled to Turkey and sent to an internment camp. She actually came to Turkey to give birth to her fifth child, which would not be allowed back in East Turkistan. Her children might have been sent to a state-run orphanage.

Maynur Memetabdulla, my cousin (female), who was born circa 1998, and her twin sister Aysha Memetabdulla were detained in late 2017 and sent to an internment camp because they have relatives in Turkey.

There were a total of 33 people in my extended family when I left for Turkey. According to the information I was able to obtain, in late 2017 only three people were not interned. The children were taken to a state-run orphanage. My youngest sister was still an infant when she was separated from my mother, and she was taken to an orphanage as well.I have not been able to contact my relatives since 2017. I wonder if they are still alive, or if they are released from the internment camps. I heard that my other relatives were also interned, e.g. from my mother’s side, my 16-year-old cousin was sent to an internment camp for the following ridiculous reasoning by an official: “Now he does not have a beard, but he may grow a beard when he grows up.”

[1] At the time, without ID cards Uyghurs could not travel between villages or counties in East Turkistan.