Following years of gradual effort made by the Chinese regime to marginalize the Uyghur language as the medium of instruction in schools and universities, it was decreed in May of 2002 that “Xinjiang University would no longer offer courses in the Uyghur language, at least in the first two years of coursework”, which was then implemented in September the same year (Dwyer 2005, 39-40; Wingfield-Hayes 2002). The Uyghur language as the medium of instruction has been reduced at all levels since 1984, while the Mandarin was only taught in minority-schools as a second language until the mid-1990s, it became the medium of instruction from third grade after the mid-90s (Dwyer 2005, 36; 38-39).

In the name of achieving “educational quality”, the Chinese government put forth ‘bilingual education’ policy in 2004, in an effort to merge minority schools with Chinese schools, simultaneously mandating that Mandarin be the primary or the sole medium of instruction, while effectively relegating the mother tongue of the minority students to the status of second language (Schluessel 2007, 257; RFA 2004). Ethnic minority teachers, both in schools and universities, were required to improve their Mandarin language skills. They also had to pass the Chinese Language Proficiency Test (also known as the HSK test), a test normally taken by foreigners. If their proficiency in Mandarin were deemed insufficient, they would face dismissal, or coercive early retirement (Dwyer 2005, 40; RFA 2004). In 2005, in most of the major cities in East Turkistan Mandarin became the sole medium of instruction across all levels of schooling, accompanied by school mergers, which could be regarded as “linguicide—the forced extinction of minority languages” (Dwyer 2005, 39), depriving Uyghurs of the choice of medium of instruction (Schluessel 2007, 260), and a direct attack on their identity.

According to Article 37 under the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Regional National Autonomy (2001), schools and other educational institutions that primarily admit ethnic minority students should, whenever possible, use textbooks written in their languages, and the medium of instruction should also be in their languages. The Chinese Communist Party, the only ruling party since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, does not uphold its own laws and constitution, which is only apt to state that China does not have ‘Rule of Law’. In addition, China also disregards international norms, conventions, and laws. Many dissidents and human rights lawyers disappear into the rightless abyss.

Based on a number of interviews conducted with Uyghur teachers by Radio Free Asia (RFA 2011, also see RFA 2010), by 2011 there had been at least 1000 Uyghur teachers who underwent unfair dismissal due to low proficiency in Mandarin in elementary schools across East Turkistan. A decade after the language policy that was first initiated in 2001, schools across East Turkistan regularly stopped offering Uyghur language education. The so called “bilingual” education really is a euphemism for mandatory Chinese education. Even Uyghur children in kindergartens could not escape the regime’s “bilingual” education campaign, an effort to effectively assimilate a whole Uyghur population. The same Mandarin-language-only curricula also apply other ethnic groups, such as Tibetans in western Qinghai province. In late June of 2017, all use of the Uyghur language was prohibited across all levels of schooling including the preschool level in the prefecture of Khotan (Hétián 和田 in Chinese), and the ban also applies to all collective/communal activities and administration work within the education system; those who violate this order would face ‘severe punishment’ (RFA 2017; also see RFA 2020b).

From September 1, 2017, following a region-wide directive entitled “The Standard Plan for Bilingual Education Curriculum in the Compulsory Education Phase of the Autonomous Region” (自 治区义务教育阶段双语教育课程设置方案 zìzhìqū yìwù jiàoyù jiēduàn shuāngyǔ jiàoyù kèchéngshèzhì fāng’àn) the so-called “bilingual” education across all elementary and junior high schools in East Turkistan started shifting to Mandarin-only education, i.e. the end goal would be that all teaching materials and the medium of instruction would be only in Mandarin Chinese (Byler 2019a). There has been an effective way of accelerating the assimilation process of the younger Uyghur generation, namely putting them in boarding schools, also known as residential schools, removing them from their familiar home communities.

In 2000 the Chinese Communist Party established twelve “Xinjiang class” (内地新疆高中班 nèidì xīnjiāng gāozhōngbān) boarding schools in the interior provinces of China, receiving students from East Turkistan, where the vast majority of whom have been Uyghurs, while the primary goal of this program has been ‘political indoctrination’ (Grose 2015, 108). Initially in the year 2000, the enrollment numbers were at 1000, and the number of designated participant cities in China proper was 12. But throughout the years the enrollment of this boarding school program has continued to increase, showing no signs of reducing. In 2020 the annual enrollment numbers are reported to reach 9880, spread across 45 cities in China proper, where the number of participant schools is to be increased to 93 (Mouldu 2020).

Similarly, closer to home in East Turkistan, almost all schools above eighth grade became boarding schools, and starting in 2017, many elementary and nursery schools also became boarding schools. Uyghur children of all ages are increasingly living apart from their parents, growing up in a Chinese-speaking environment, deprived of a family upbringing in the Uyghur language and native culture. This education system is “stealing a generation of Turkic Muslim children from their native societies” (ibid.).

Studies (Reyhner & Singh, 2010; Woolford, 2009) on residential schools have demonstrated that this type of education system is conducive to eliminating native languages, religion and cultural knowledge, which is a form of cultural genocide. The Chinese regime’s increasingly intense efforts to integrate Uyghurs into the Han majority population at the turn of the 21st century are decidedly more assimilationist than its minority policies in the 1980s.

These illegal directives from the Chinese regime violate China’s own law, for example Article 10 in addition to the abovementioned Article 37 under the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Regional National Autonomy (2001).

One could argue that there exists an economic incentive for Uyghur school kids to have higher proficiency in Mandarin, a conduit through which they can achieve employment and higher living standards later in life. This argument has a gaping hole in it, assuming that proficiency in Mandarin will lead to future employment, well however, reality begs to differ. As a matter of fact, there is a widespread discrimination in the job market against the Uyghurs and other minorities. It is not uncommon to read “hiring only ethnic Han Chinese” in a job vacancy advertisement (see UHRP 2012, 4-6). In state sectors, most of the available job vacancies are reserved for Han Chinese (CECC 2009). “[E]mployment opportunities have become increasingly scarce for Uyghur applicants, regardless of [their] language proficiency [in Mandarin] (Smith Finley & Zang 2015, 17; also see Smith Finley 2007, 220).

Zang (2011, 154-55), a Han Chinese scholar, finds in his analyses of income gaps that in the city of Ürümchi, in general, Uyghurs make 31% less than Han Chinese. In the whole of East Turkistan Uyghurs make 52% less than Han Chinese in on-state sectors. He also finds that discrimination is a more plausible factor in accounting for the income inequality, rather than schooling background. His findings confirm what many Uyghurs have experienced and suspected for a long time, feeling marginalized in their own land and not enjoying their share of the economic advancement.

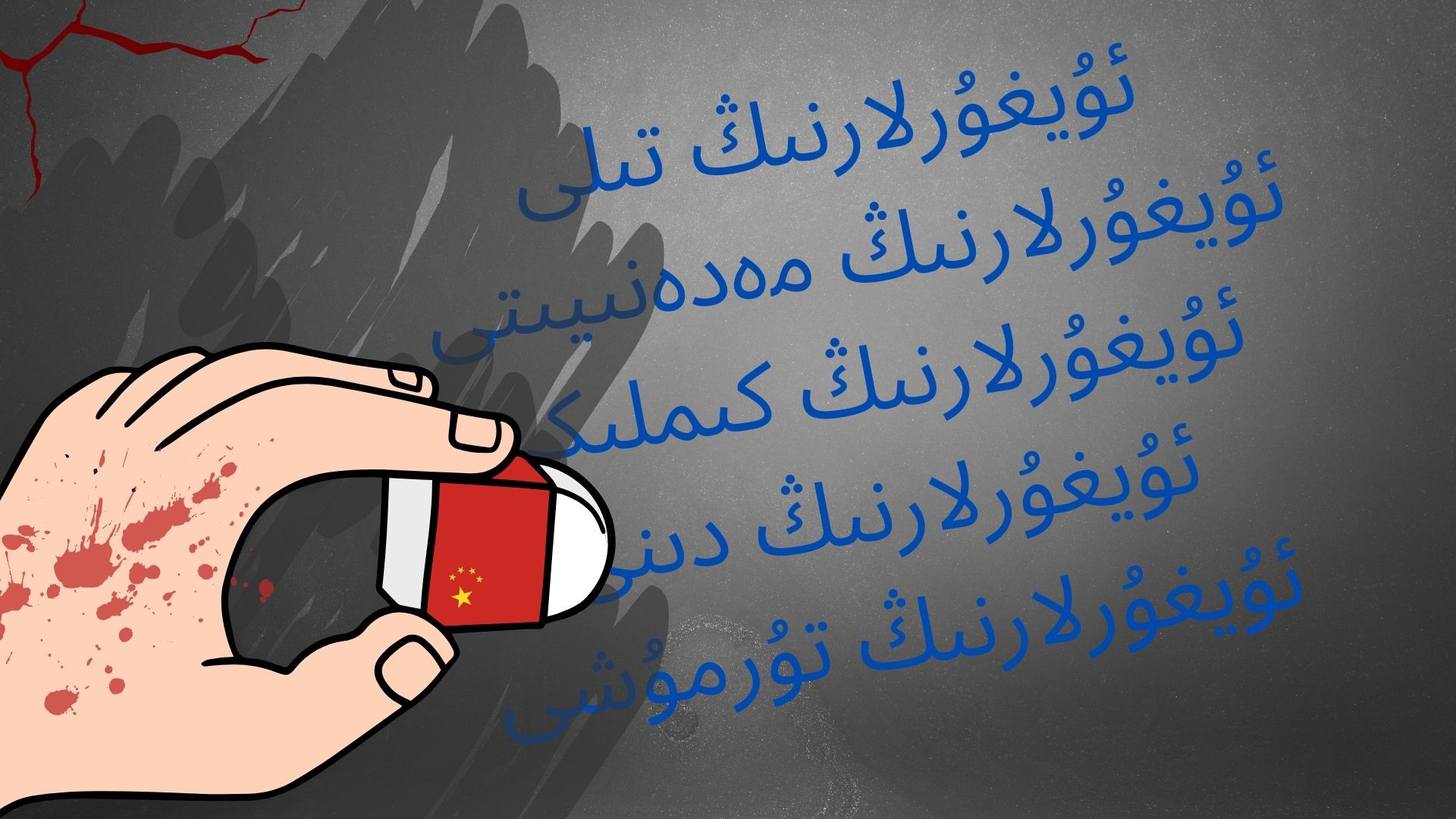

Scholars have consistently demonstrated that the Uyghur language is paramount to Uyghur identity (Smith 2000, 155, 157-61; Smith 2002, 159-61; Dwyer 2005, 59; Hess 2009, 82; Schluessel 2007, 260; Reny 2009, 493-4). The abovementioned assimilationist policy of the Chinese state in making Mandarin the only medium of instruction in schools and universities will only contribute to the further divide between the Han Chinese and Uyghurs. “Any credible educator will agree that schools should build on the experience and knowledge that children bring to the classroom, and instruction should also promote children’s abilities and talents” (Cummins 2001, 16). The research on the importance of bilingual children’s mother tongue development is uncontroversial in that one’s personal growth and educational development are greatly shaped by their mother tongue; the mother tongue proficiency will in turn contribute to their second language development (ibid., 17). “Bilingual children perform better in school when the school effectively teaches the mother tongue and, where appropriate, develops literacy in that language” (ibid., 18).

Learning a second language is beneficial, but it should only occur on one’s own volition. There must be other language policy solutions available to the Chinese regime if it so chooses to adopt, where Uyghurs can achieve higher proficiency in Mandarin while simultaneously developing a good command of their mother tongue by retaining the choice with respect to the medium of instruction. Furthermore, “Increased autonomy is a workable solution which, though apparently in conflict with the tenets of current CCP ideology, will be necessary in the near future in order to avoid widespread language grief among an already restive populace” (Schluessel 2007, 273).