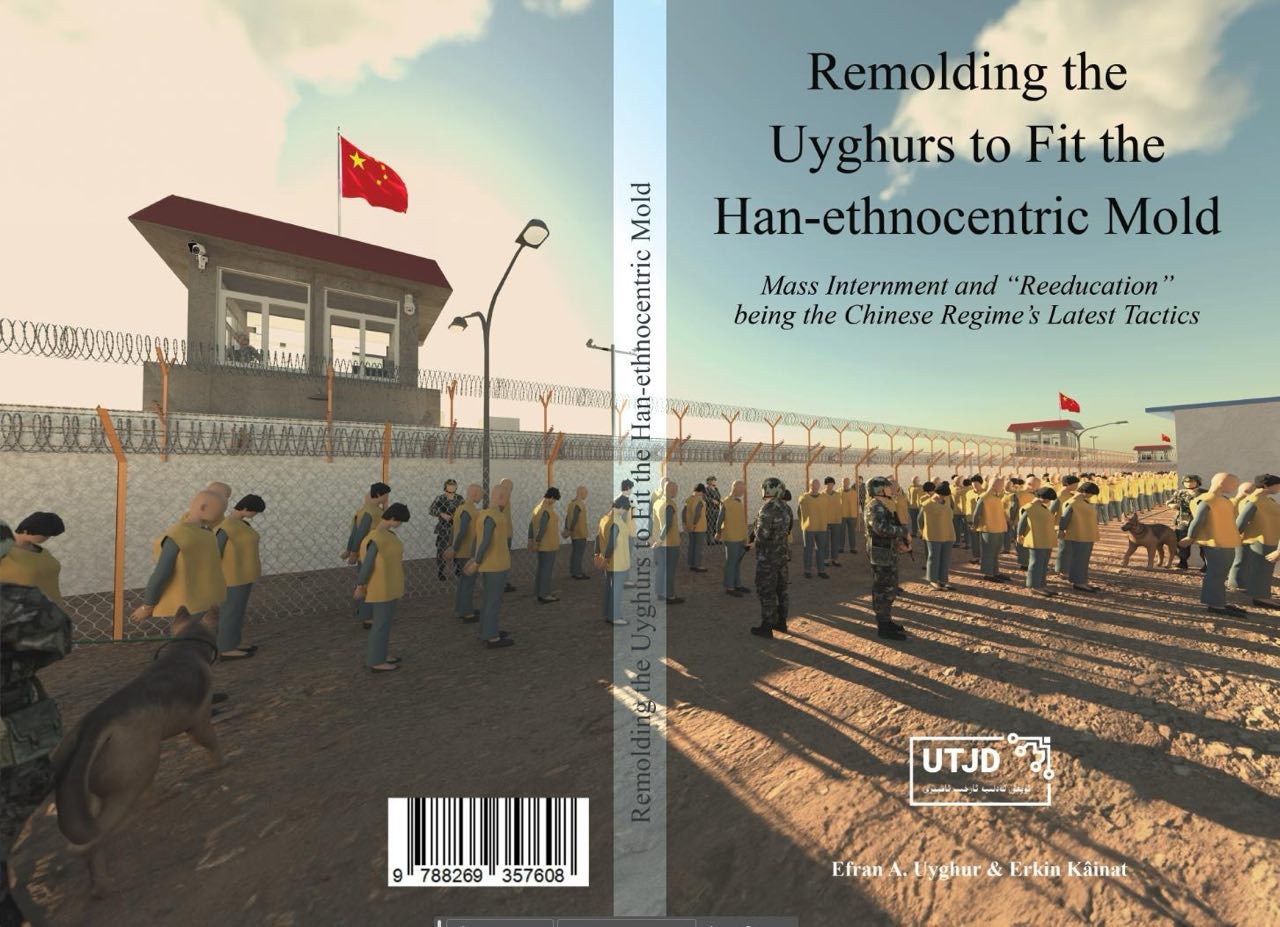

Forced labor, as it was slowly being rolled out since the summer of 2018, became the next chapter of the Chinese regime’s efforts to subjugate a large swath of the Uyghur population. As one batch of “trainees” graduates from the mass internment “re-education” camps, there must be one batch of “trainees” in employment/work (结业一批就业一批), according to a leaked internal Chinese document.45 “Jutting out against desert dunes, the new industrial zones in Xinjiang are often surrounded by high walls, barbed wire and security cameras. Some are built near indoctrination camps and employ former inmates” (Buckley & Ramzy 2019).

Many previously interned had been released from the internment camps, only to find themselves held captive and trapped in various forms of forced labor (Zenz 2019d). As The New York Times reported back in 2018 that “[t]he inmates [from the mass internment camps] assigned to factories may have to stay for years” (Buckley & Ramzy 2018). In his research based on Chinese government documents, Zenz (2019d) yet again presents to the world the Chinese regime’s relentless drive to erase Uyghur identity, which includes an amalgamation of forced labor, family separation, and social control over Uyghur families, while executing all these state-directed measures in the name of “poverty alleviation”.

The forced labor program operates in parallel with the mass internment indoctrination camps (Buckley & Ramzy 2019).

Zenz (2019d) in his research has identified three major routes to forced labor through indoctrination (political indoctrination and thought reform on religiosity) by which the Chinese regime subjects a large swath of the Uyghur adult population as well as other Muslim minorities to forced labor with varying degrees of coercion:

- With the highest coercion level, internees are released from internment camps and sent to forced labor in camp-adjacent factories or close-by industrial parks, and subsequently may then be sent to their home regions’ forced labor factories;

- Targeting mainly the general rural population, adults of working age who are able to work are first sent to centralized training programs that include thought reform and ideological indoctrination, and then to forced labor thereafter;

- With arguably the most intrusive social re-engineering aim in mind, having the most detrimental impact on Uyghur society, accompanied by a form of involuntary labor with relatively weaker direct evidence of coercion than the two abovementioned, Communist Party work teams in villages “encourage” people (especially women) to take full-time factory jobs in various ways, while their children are placed in state-run child care facilities.

In spite of varying degrees of coercion, the overarching objective of the three abovementioned routes to forced labor is to serve ‘government social stability needs’ (政府出于维稳的需求) through thought reform and Communist Party ideological indoctrination, as it is indicated in various government documents (Zenz 2019d).

In the case of the third route to forced labor, the so called satellite factories in rural villages, like other forced labor factories elsewhere in East Turkistan, are likely to be equipped with high security features, such as fences, surveillance apparatus and metal detectors, according to what were previously publicly available advertisements to construction companies as well as procurement bids. Chinese regime’s “poverty alleviation” measure “promotes a significant degree of separation of children from their parents – at least during the work days” (ibid.). Almost all satellite factories in villages have day care centers where pre-school children can go to while their parents work at factories. Zenz (ibid.) argues that forced labor occurs in a state-controlled milieu, greatly reducing family interaction, thereby diminishing “intergenerational cultural, linguistic and religious transmission”.

According to a video reporting by The New York Times (Buckley & Ramzy 2019), many Uyghurs as well as other Muslim minorities (but mostly Uyghurs) have been sent to forced labor from the south of East Turkistan (e.g. Kashgar and Khotan), where most Uyghurs live, to mostly Han-Chinese populated north (e.g. Kuitun). “There is a great deal of pressure placed on individuals to sign work contracts. The threat of the camps hangs over everyone’s heads, so there is really no resistance to assigned factory work,” said Darren Byler, an expert on East Turkistan (ibid.). In the video, one worker says that he now only makes a third of what he used to, in comparison with his income back home in the south. One Kazakh worker named Erzhan confirms the exploitation by stating that “[he] worked on a production line for 53 days, earning 300 yuan ($40) in total” (Byler 2019c). “The goal of the internment factories is to turn Kazakhs and Uyghurs into a docile yet productive lumpen class — one without the social welfare afforded the rights-bearing working class” (ibid.).

“Government documents blatantly boast about the fact that the labor supply from the vast internment camp network has been attracting many Chinese companies to set up production in Xinjiang [i.e. East Turkistan], supporting the economic growth goals of the BRI [the Belt and Road Initiative]” (Zenz 2019d). While in eastern China where fewer people want menial low-skilled factory jobs, East Turkistan offers not only government subsidies and generous tax breaks but also inexpensive labor (Buckley & Ramzy 2019).

According to a recent report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (Xu et al. 2020), in the period 2017 to 2019, more than 80000 Uyghurs had been transferred out of East Turkistan to China proper, assigned to many different factories via the Chinese government’s labor transfer program called ‘Xinjiang Aid’ (援疆).46 The report has identified 27 factories across 9 Chinese provinces that have been using Uyghur forced labor, manufacturing products for 83 global brands, including Apple, Nike47, Gap and Sony. The relocated Uyghur workers cannot opt out easily as this labor transfer program is closely linked to the Chinese regime’s mass internment drive in East Turkistan, where defiance highly likely would send them to one of the internment camps.

On July 19, 2020 another exposé by The New York Times revealed that Uyghur forced labor was used, through the controversial state-directed labor transfer program (also known as the “poverty alleviation” program), by a number of Chinese companies manufacturing personal protective equipment (PPE) to meet both the growing domestic and global demand as the COVID-19 continues to run rampant worldwide.48 As of June 30, 2020 more than 17 companies out of the 51 in East Turkistan take part in the coercive labor transfer program. Moreover, The New York Times also traced and identified several other companies in China proper (e.g. Hubei province) that use Uyghur forced labor to produce PPE.

Source: “The persecution of Uyghurs in East Turkistan” Authors: Erkin Kâinat; Adrian Zenz; Adiljan Abdurihim Link: https://www.utjd.org/register/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/the_persecution_of_uyghurs_hard_copy.pdf

Image: Canva