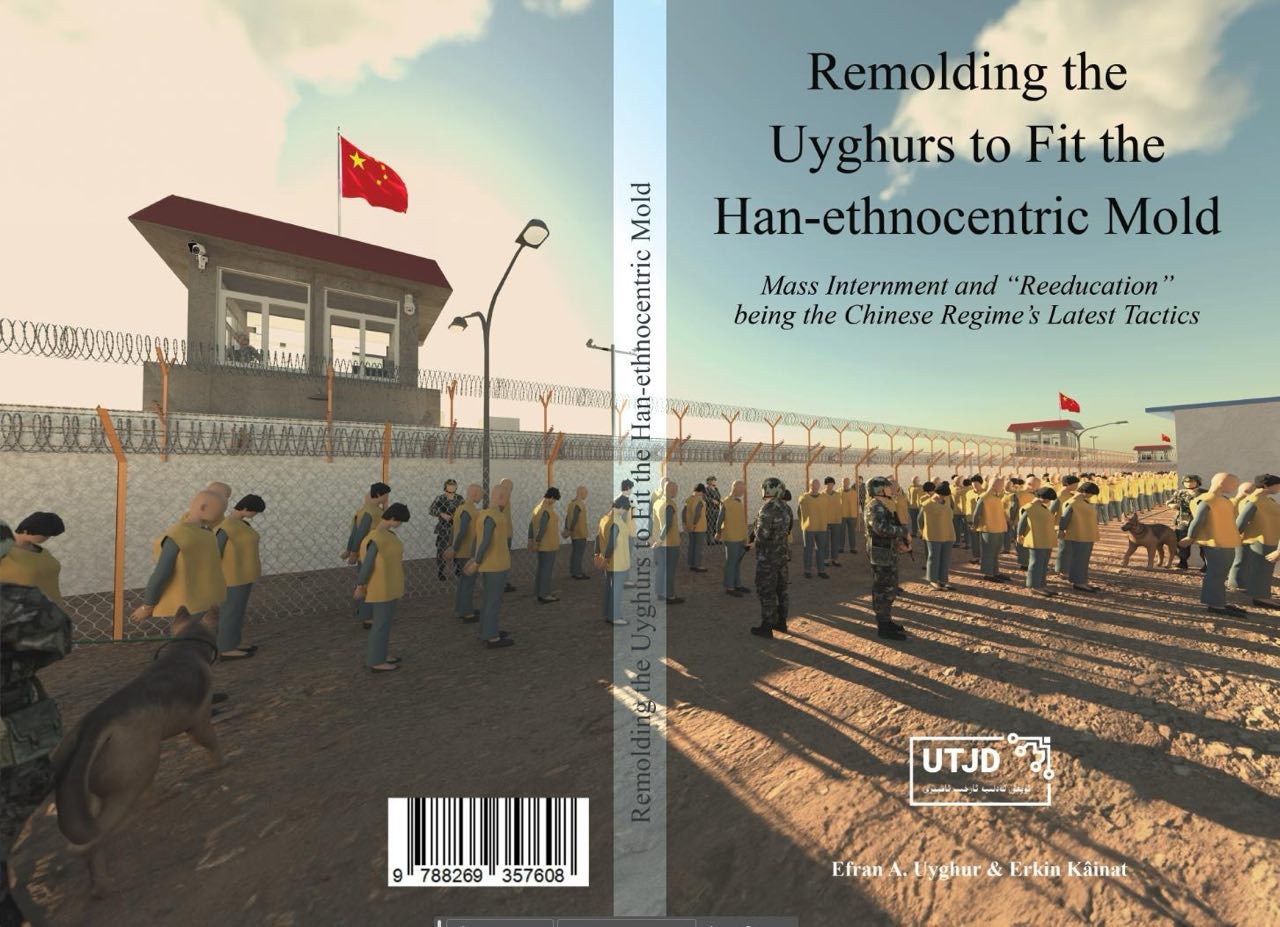

We have self-published our second book— Remolding the Uyghurs to Fit the Han-ethnocentric Mold: Mass Internment and “Reeducation” being the Chinese Regime’s Latest Tactics. This book was well under way with respect to its research prior to the release of our first book— 100 Camp Testimonies. Since its inception back in 2017, UTJD has been gathering testimonies mostly from the Uyghur diaspora. At the peak of the Chinese regime’s mass internment campaign, coupled with the expansion of our team, we also started to systematically gather data and document suspected internment sites across East Turkistan. We had gathered data points on various types of internment sites, ranging from their geographical coordinates to their sizes and security features at different times. With regard to the estimation of internment capacity, we had to painstakingly calculate the capacity for each of the suspected 843 internment sites, based on the satellite imagery data.

We start off the book with one former Uyghur internee’s ordeal, one story out of at least a million Uyghurs that had been sent to various types of internment facilities. By recounting one individual’s ordeal, we want to invite the readers to dare imagine the similar tragic stories of countless many other Uyghurs. In the next few chapters, we provide readers with historically essential facts and perspectives on East Turkistan’s colonial past, as well as the interactions between the Chinese regime (the oppressor) and the Uyghurs (the oppressed) in recent history, with varying degrees of intensity, painting a picture that shows the trajectory of the assimilation of the Uyghurs. The main focus is placed on the Chinese regime’s intensified persecution of the Uyghurs since the 2010s, when there was a clear shift in the regime’s approach, the one that intended to forcefully remold the Uyghurs to fit the Han-ethnocentric mold. In the methodology section of the book, we lay out in details the methods used in the UTJD’s research, which primarily relied on the satellite imagery data.

This book aims to contribute, in the context of settler colonialism as well as China’s nation-building, to understanding how the Chinese regime’s mass internment of Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in East Turkistan, the most oppressive securitization efforts to date to preemptively punish and persecute the whole Turkic Muslim populations, is meant to speed up the remolding process and to impose the homogeneous national identity known as Zhonghua Minzu (the Chinese race) on all. Our own research on the camp system presents the spatiotemporal changes of the identified various types of internment sites as well as the statistical data on how many of them were suspected of using forced labor.

We have been able to identify 843 suspected internment sites of various types and gathered as much information as possible about them. Depending on their type, these identified internment sites were in turn grouped into the following 10 categories: reeducation internment camps, general prisons, general women’s prisons, sick-inmate prisons, juvenile correctional facilities, reform through labor prison farms, reeducation through labor camps, administrative detention centers, pretrial detention centers, and compulsory isolated drug detoxification centers. The camp system in East Turkistan is composed of various types of abovementioned internment facilities as arbitrarily interned Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples have been sent to all of them.

The identified various types of internment sites have seen changes in number, area size, security level, and capacity over the years, and in the section overall findings we have presented and analyzed the data for each of these changes leading up to the year 2022. The upward trends in results across the board regarding various types of internment sites consistently correlated with the start of the Chinese regime’s mass internment campaign, except for reeducation through labor camps, an outlier that mostly saw no changes in number, area size, and security level, but saw a dramatic decrease in capacity between 2017 and 2018, and an increase in 2019, after which the capacity remained more or less the same until 2022.

In order to salientize the regional differences in internment capacity and the extent of XPCC’s (the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, or Bingtuan) involvement in the Chinese regime’s mass internment drive, we also presented the data for various cities, prefectures, and XPCC divisions. The pattern emerged from the data shows that southern East Turkistan had the highest estimated internment capacity, which was by no means a surprise as the majority of the Uyghur population reside in the south. With respect to the use of Uyghur forced labor in various types of internment sites, we identified 32 reeducation internment camps suspected of using forced labor in 2017, and two years later there were almost four times as many, reaching 124, which remained more or less the same until the year 2022. The internment facility type that had the second most suspected forced-labor factories were reform through labor prison farms, with 46 such internment sites suspected of using forced labor in 2022. The number of suspected forced-labor factories affiliated with identified general prisons, reeducation through labor camps, general women’s prisons, and juvenile correctional facilities in 2022 were respectively 19, 5, 4, and 2. Lastly, we haven’t identified any forced-labor factories affiliated with any identified detention centers.

We are very please with how this book turned out. We hope that, by reading this book, readers will come away with a better and deeper understanding of how Uyghurs have been subjected to the forced remolding and state-sponsored persecutions in their homeland East Turkistan, informed by historical facts and perspectives.